For 2021 our Kindy research question was: “Building relationships with Country, people, language and place through many stories.”

“Stories are at the centre of human connection. We have always used stories to connect emotionally, person-to-person and make sense of our chaotic, ever-changing world. As humans, we can’t help but gravitate toward the emotional pull of a great story.

Telling stories helps us relate to our world. It defines and illustrates our experiences and binds us through our one commonality – our humanity. Stories have the ability to transcend language and culture by evoking emotion.”

– Connecting Emotionally Through the Power of Storytelling

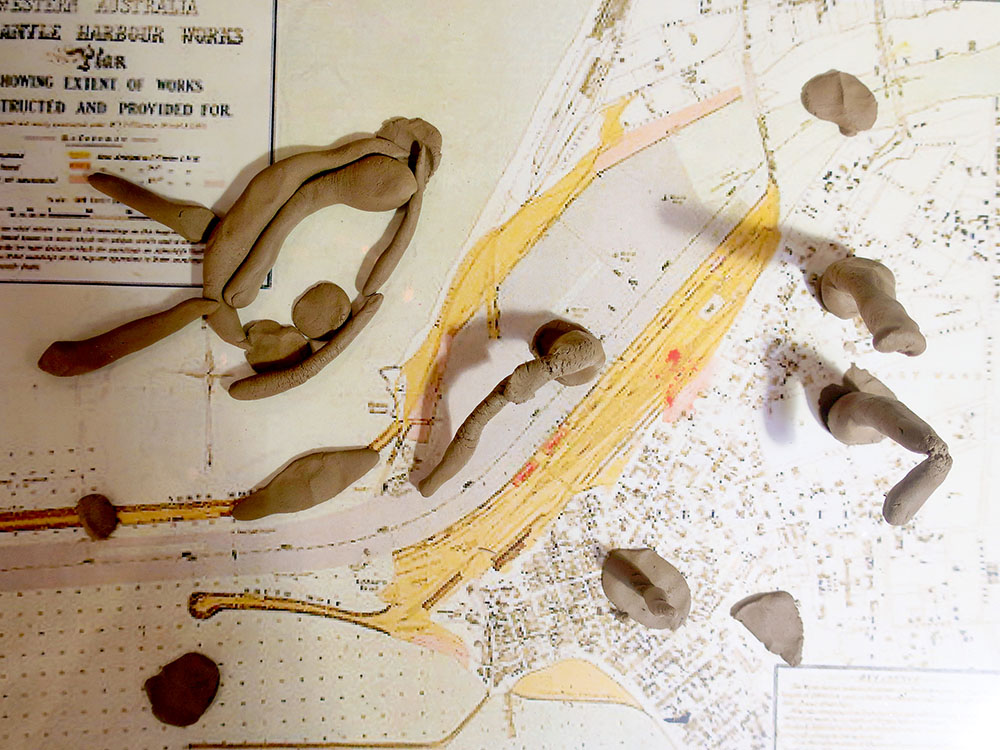

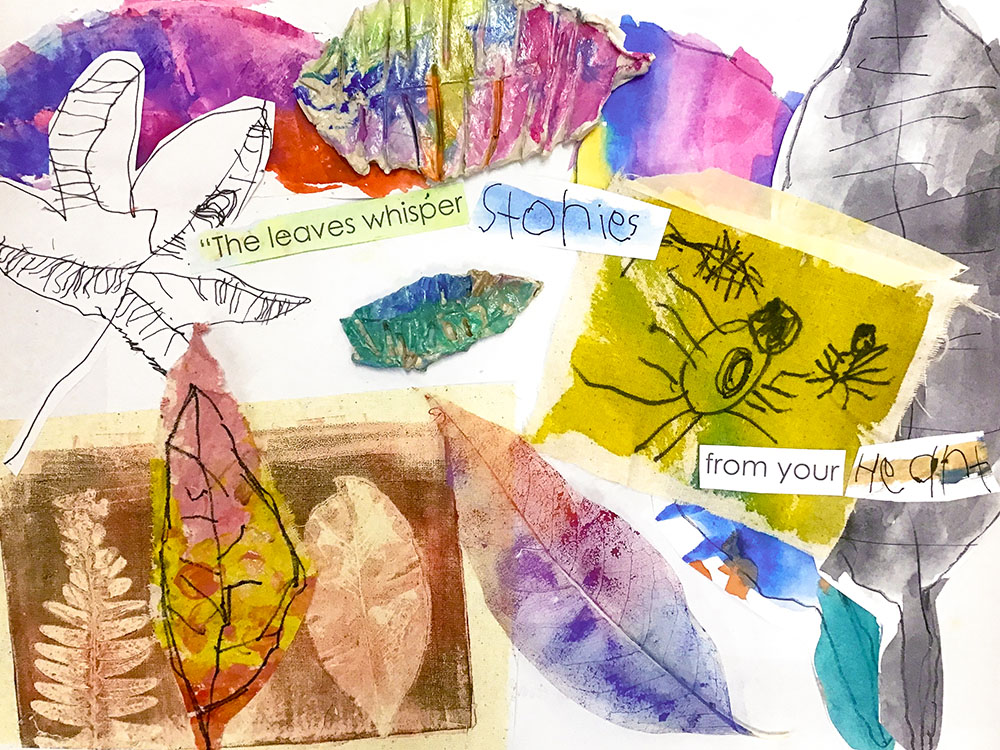

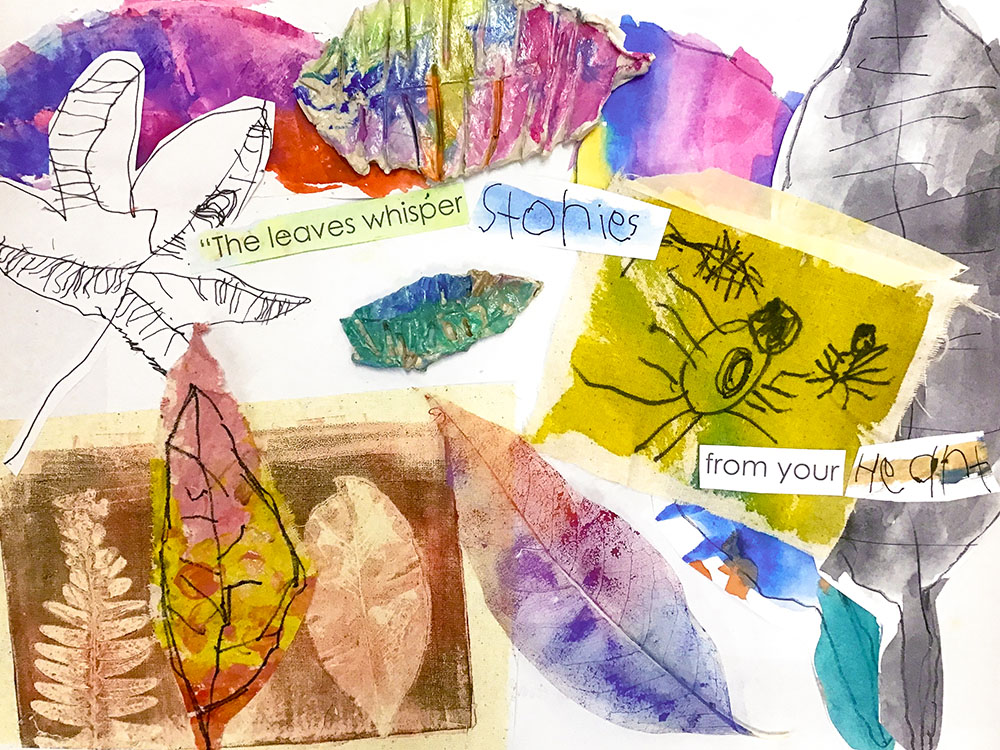

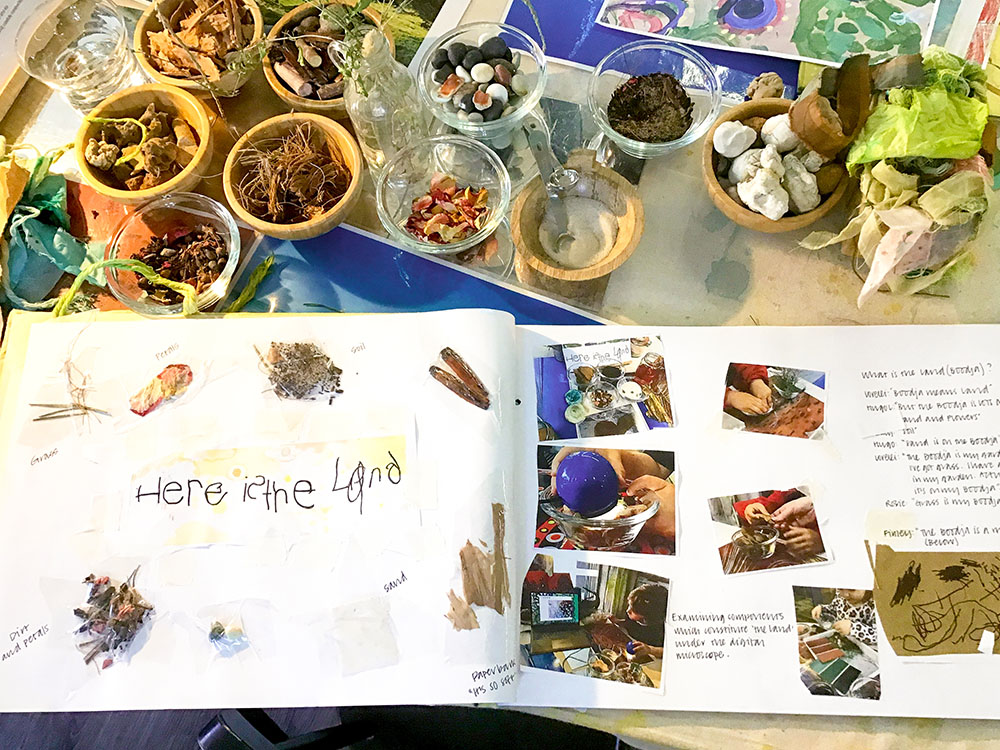

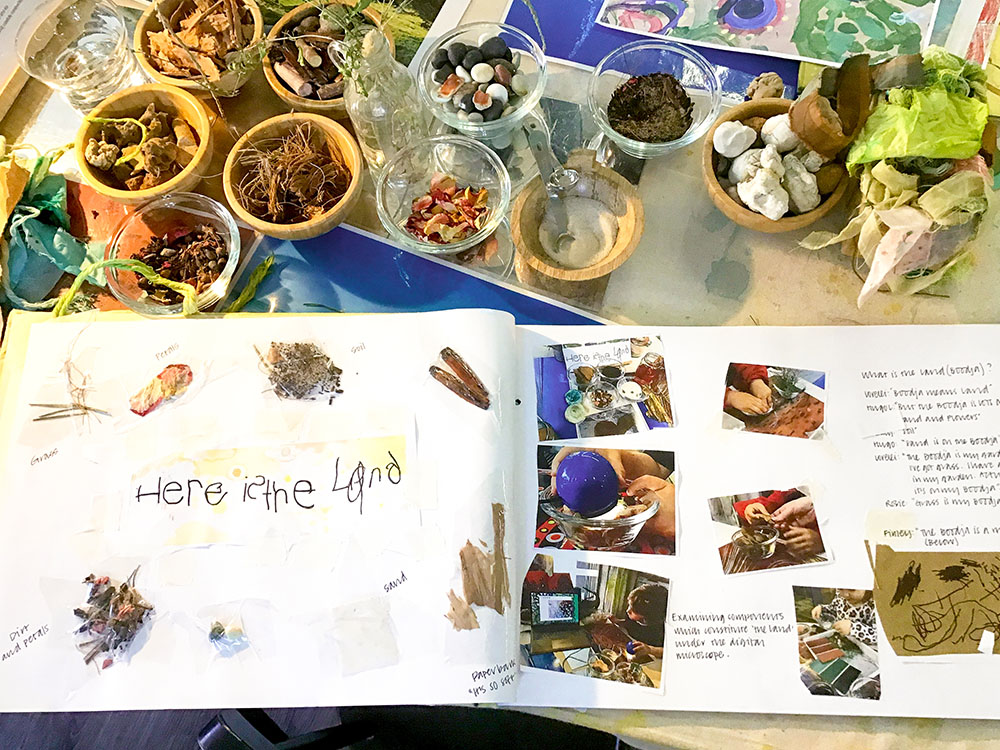

During this research, the children in the Kindy programmes have engaged with many ways of telling a story to understand and express their connections to families, friends, local community, land and Australia’s first nation’s people. Some of the diverse mediums the children and educators have used to engage in this research include mapping, puppetry, shadow stories, woodwork, collage, clay, dance and song.

The educators chose specific intentions (concepts, dispositions, skills) essential to learn when engaging in this big idea. These intentions are as follows:

- Concepts of Relationship, community, Responsibility and connection

- Dispositions of Caring, curiosity, interdependence, and creativity

- Communication and thinking skills: Language, singing and observing

- Personal and social skills: Considering others, taking action, safety and taking responsibility

- Research skills: Creating, exploring, collecting data and creating

- Actions: Reflection, sharing information and advocacy

Educators met many times this year to discuss and share their learning journeys. For the last meeting, the Kindy teams, Studio educators and Liz, Louise and Pia (members of the Pedagogy and Training team) met to identify research findings.

The following findings emerged through the children’s work and their stories.

3-Year-Old Kindergarten

Family is Everything

For younger children, we discovered that family is everything. It is an extension of themselves and their lens to understand the world. The children used this lens to connect to Country and people. Children observe nature and Country through family grouping and the disposition of caring.

Family members, mum, dad, siblings, grandparents, were included in all aspects of the children’s work. Educators observed this family theme repeatedly when the children discovered insects around the centre.

The children’s first thought was considering where the insect’s family may be: “Where is its mum?”

The children’s interest in insects’ families extended to their concerns about their well-being. The children also expressed the concept of the family when talking about plants and trees. In addition, children wondered whether other living things were hot or cold, whether they needed food, and whether they had a home.

Conversations continue to hypothesise about family and creating safe places, a home, for the insects to inhabit.

Children’s Conversation

Nikhil: “The man came and got the web away.”

Clara: “He needs to live in it. He’s got to have a house.”

Sophia: “He needs to climb up there, with mummy and daddy spider. He needs to go with the family.”

Emma: “And with sister and grandma and the whole family.”

Darragh: “We’ll have to open the door for him.”

Emma: “She’ll need a blanket and a dummy to sleep with.”

Sofia: “The spider needs his house to be safe.”

Emma: “But it doesn’t have a roof.”

Sofia: “We need to make a roof. A roof for the wind and rain.”

Emma: “The spider has to stay dry.”

Sofia: “We need to save the spider.”

Nikhil; “I made a trampoline so the spider can jump onto our hands. The spider can jump down and go on a bike, into the car and the bike and then jumped into his house.”

Darragh: “I made a cosy looking roof on top of the flags so he can watch TV.”

Nikhil: “You know spiders can make webs ….. and Spiderman can,”

Nickhil 3 years 2 months, Clara 3 years 5 months, Sophia 3 years 4 months, Darragh 3 years, Emma 3 years 1 month

Family Language

What became apparent through the children’s stories of their family was the importance of family names and titles and the value they hold to the children.

The children shared some words from languages they spoke at home. They shared the specific words attributed to their family members, such as Oma, Opa, Gran, Poppa, Mumma, etc. The children became upset with mispronounced titles, reflecting the significance of these words. They would then correct the educators on their mispronunciation.

Children saw the title given to significant family members as only pertaining to them and their world. They were not universal names and titles. So often, when grandparents had similar designations like Nanna, the children debated whose Nanna it was.

“It is my Nanna.” “No, it is my Nanna.”

‘Family is everything’ was also demonstrated in the children’s attachment to siblings or extended family names. Children became upset when another child would use a person’s name, which the child believed only belonged to their family. Educators were sensitive to the importance of this for each child. As a result, they planned further opportunities to expand children’s concept of family.

Connecting through Food Stories

The children’s food stories became a social commonality and reference point. These food stories allowed them to build relationships and connections with places and people outside their families.

Food eaten at home became the children’s way of connecting to find common ground. In the Kardan (North Perth) room, Yonka (Kangaroo) travelled home with each child to share adventures with the child and their family. Upon Yonka’s arrival back at the centre, the children shared many stories of Yonka’s time with them. What became apparent was the children’s focus on the delicious treats Yonka enjoyed with the family. The children delighted in hearing about Yonka’s meals.

The Fire Dragon created in Poppy (Como) also had specific food tastes that the children enjoyed sharing. Once again, this created a common language through which to explore their connections with each other.

The mealtime cards and book used in Karella (Subiaco) highlighted the role food played in constructing a community connected through their interest in different food and the mealtime process.

“A big Daddy spider. He’s eating bananas.”

– Audrey C, 3 years 3 months

“Dragon is in teacher’s room because he loves crackers and biscuits.”

– Maanvi, 3 years

“Dragon is in the soil. It eats worms.”

– Izaak, 3 years

“I can share ice cream (with the Dragon)”

– Quinn, 3 years

“The rainbow snake needs a placemat…and colourful food… Rainbow snakes need colourful food to become colourful”

– Leni, 3 years 9 months

Connecting to Country

A significant finding was the children’s dance of identity. This dance begins between the nesting, security, and familiarity of the known, contrasting with their awareness of their own way of being and its risk.

Children connected to Country through exploration and investigation into the six Noongar seasons. The Mia Mias, shelters, and the season of Makuru became essential connections for the children. Along with how the children’s lifestyles changed depending on the season. For example, in Bunuru, when it is very hot, the children remember going to the pool and the beach becoming intuned with those memories. The children role-played and re-enacted the seasons, building cubbies and ideas of sheltering around the Makuru season.

The child’s house was the most crucial place. It symbolised security and safety. Building nests, cubbies and houses from clay, construction materials and blankets was a feature of their play and stories. The younger children showed their courage and risk-taking when exploring ideas of leaving the nest and becoming more independent.

“The baby bird is happy because his mum is bringing food for him. My mum and my dad also bring food for me in their hands.”

– Maya K, 3 years 11 months

“I made a trampoline so the spider can jump onto our hands. The spider can jump down and go on a bike, into the car and the bike and then jumped into his house.”

– Nikhil B, 3 years 2 months

“I like Djiti Djiti birds (Willie Wagtail). I m going to make a nest for me and my friends, so we can be little Djiti Djiti birds … I want to make a nest for my friends and myself. We are going to be five little birds looking after the eggs and shelter them”

– April, 3 years 11 months

4-Year-Old Kindergarten

Mapping Inquiry

We found that home represents me, family, protection, and place for our older children. All roads lead to home. Home symbolises belonging. Belonging is the lens through which they understand the world.

Centre’s developed mapping inquiries throughout this research to build a relationship with place. Some schools engaged in community walks, visits to the city, the train station, community garden, or local parks. Their homes were always part of their storytelling during the children’s conversations and reflections on these places. Children talked about the distance between these spaces and places in relation to their homes and school.

‘Home’ was carried with them in any encounter within their community and used as a lens to reflect, collect data, connect and become knowledgeable.

Numbats (Nedlands) engaged in mapping the many train stops on their way to school. In Matisse (West Leederville), they mapped the significant places in their community and their interdependence with one another. Other centres (Subiaco, Como, North Fremantle and North Perth) focused on mapping the community within the school.

“My house is actually on South Street…around the corner and around the wiggly bit.. and across the tunnel… then down that road… then turn that way then you are at my house,”

– Abel, 4 years

“This is my house, my neighbour’s house and my friend’s house down there. I take the care to go to my friend’s house, and there is lots of flowers on the way back to my house. Mum is going to plant some flowers in our garden.”

– Indie, 4 years 4 months

Connecting to Country

Country became a place of belonging. Hence the children’s desire to take action on behalf of Country and of things that belong to them.

For the kindy children, a place mattered once we invited them to engage with it repeatedly, observing its changes, adaptability, weather, and the animals in it. Visiting the same place in their communities for an extended amount of time helped the children understand and know a place in Country better. Additionally, developing a sense of belonging to it in the process.

“Hey, this tree doesn’t have leaves anymore, where did they go?”

– Joseph, 4 years 10 months (on the way to Mueller Park)

“That’s because it’s Djilba, there’s tiny new leaves growing,”

– Helena, 5 years 2 months

“It must of got cold in winter (Makuru),”

– William D, 5 years

“I wonder if the leaves will be bigger next time.”

– Emily, 4 years 9 months

Giving Country a Voice

By mixing fantasy elements and real-life experiences in their storytelling, children offered a voice to Country. We found that for older children, ‘place is me.’ ‘Place’ does not have any geographical attributes and is intrinsically attached to their relationships and experiences with the people in their lives. Children’s identity is therefore braided together with place.

Children’s Relationships with Country develop through wondering about the interrelation between nature’s elements and stories of friendship. During this process, they personified nature whilst exploring aspects of their identity such as gender, feelings and emotions.

Examples of these findings:

- North Perth | Wolgol’s story of the whispering tree

- North Fremantle | The sculpture to invite the wind by Clontarf

- West Leederville | The tiger and the tree story by Matisse

“Where the Boodja and the worl come together is like a meeting place, because they are friends. The worl makes the rain for the Boodja”

– Charlotte D, 4 years 7 months

“The wind comes out because it’s a rainy day, the wind and the rain they always recognise each other, they think they are best friends”

– George J, 4 years 9 months

“All the purple flowers are moving. They are dancing for us. They are happy to see us visit”

– Luciana M, 4 years 11 months

“I am Fremantle”

– Milly H, 4 years 2 months

The children’s stories of Country and places in Country were often collaborative, reciprocal and intertwined.

Places also became acknowledged and named for what they represented to the children:

- ANGOVE ST | “The road with the coffee.”

- HYDE PARK | “The Water Fountain Park”. “The little park and the big park,”

- COMMUNITY GARDEN | “The frog place” “Every people’s garden, the one with the swing.”

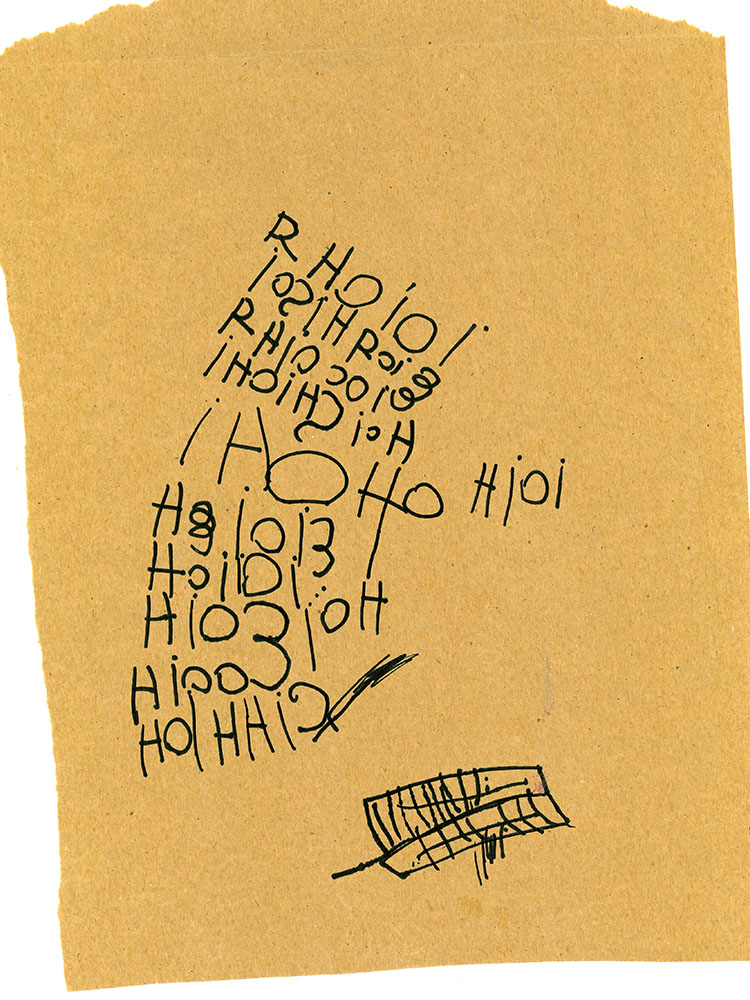

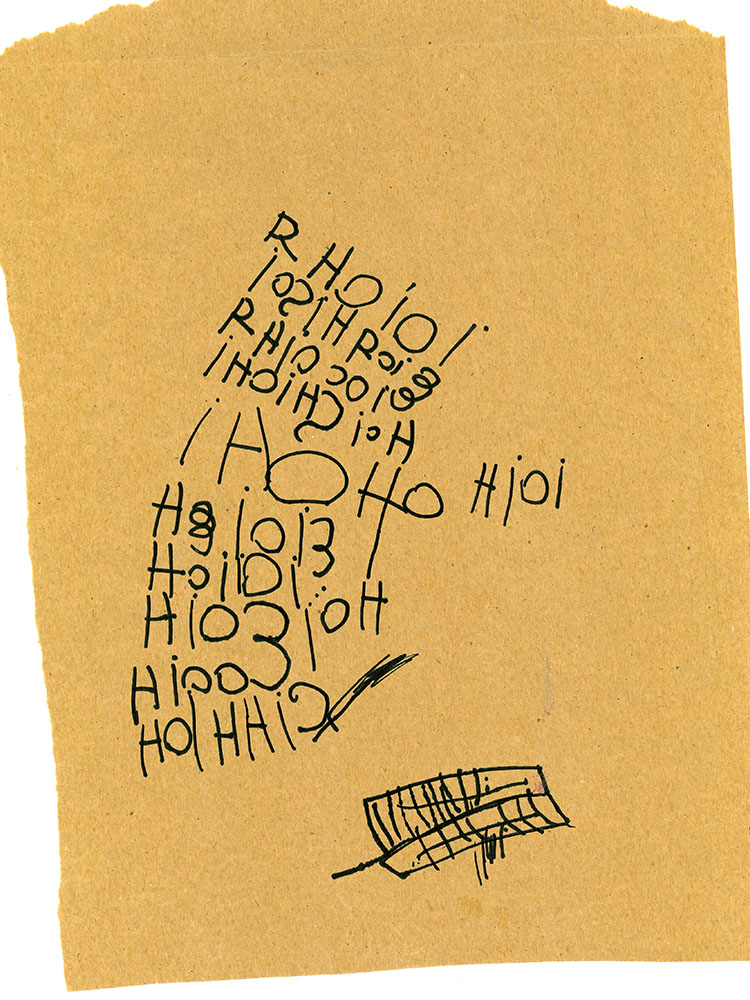

Symbols and Meaning

Another significant finding was the children’s acknowledgment of the meaning in and of symbols. As a result, this builds depth to their understanding of place. Signs, symbols, and universal representational imagery became a communal shared language. As the children developed their relationship with “place” and Country, they also noticed and became curious about place numbers, names, and signage.

The children’s emerging literacy skills and new written language became a way of understanding place, and a means for social participation.

Examples of these findings were:

- Como | Preston’s Acknowledgment of Country

- West Leederville | Matisse’s encounters during their community walks

- North Perth | The Acknowledgment of Country song by Wolgol

- Nedlands | Train stations to Lock street by Numbats

Educators also found that particular words, songs and sign language (Noongar language, Australian sign language) became the norm when talking about certain things or aspects of Country. Educators used Noongar words with purpose and in context. As a result, children began to integrate such language seamlessly into their everyday vocabulary, often correcting educators and peers when used in the wrong context.

“Whadjuk Country is Perth, and Noongar People say different words to us, and it’s just a bit different than Spanish”

– Cova, 4 years

Acknowledgment of Country in Auslan

As the children connected to places in their community, we witnessed how they gave voice to their desire to advocate and protect Country. Matisse’s (West Leederville) story of protecting their Gumtree meeting place in Mueller Park exemplifies this finding. Kanimbla’s (Subiaco) addition of animals to their Acknowledgment of Country is another example.

“The tigers might sneak at night and scratch the trees, they hide in the garden, but that’s our special tree”

– Charlotte D, 4 years 7 months

“Nooo, it’s getting more scratches again – We have to protect it – These (sticks) have to go here”

– William D, 5 years

“With some sticks all stacked?”

– Joseph O, 4 years 10 months

“Yeah, all around, so it doesn’t get more scratched on the other sides”

– Max I.G, 5 years 5 months

“The old tree said to me, ‘Sorry Emily, you can’t pick things anymore’, so we can’t take from Noongar land because it’s still growing. Hey Charlotte and Isabella, we need to go ask another gum tree if we can pick things because this one doesn’t want us to take too many nature things”

– Emily T, 4 years 9 months

Previous Studio and Kindy Research

Connection to Land and Country: Studio & Kindy Research 2020

SOEL 3 and 4-year old kindy’s “Connection to Land and Country” 2020 Big Idea explored the Noongar seasons, Yarning Circles and Reconciliation through research.

Woven Connections: Studio and Kindy Research 2019

Using the city as a provocation, SOEL Kindy children used existing investigations to draw meaning and understandings of the place they live in.

Yagan Square: Studio and Kindy Research 2018

Yagan Square News – SOEL Kindy children will present a gift to the city in the form of a 10-minute video presentation to be played on the Digital Tower.